Choosing Teapots - A Quick Guide to Shapes and Materials

Making tea is, at its core, the careful release of flavour from the tea leaf. In traditional Chinese tea-making—known as Gongfu Cha (Tea with Great Skill)—the teapot plays a central role in this process. Size, shape, clay type, and firing temperature all influence how heat is retained and how the leaves unfurl and must be chosen to suit the type of tea and the number of people being served.

What To Look For When Choosing A Teapot

Serious Gongfu Cha enthusiasts can spend hours debating teapots, but there is broad agreement on a few essential principles that guide good choice and long-term use.

First, clay teapots are widely regarded as the best vessels for making tea, with the most prized examples made from Purple Clay (Zisha) sourced from Yixing. Zisha clay is naturally porous and manages heat exceptionally well, qualities that noticeably enhance flavour compared with glass, porcelain, or glazed teapots. For this reason, a Yixing teapot should be dedicated to a single type of tea. Over time, tea oils are absorbed into the unglazed clay, softening the brew and adding depth. Mixing different teas—especially those with strong aromas—can cause flavours to overlap and diminish more delicate teas.

Firing temperature also matters. High-fired teapots, made with finer, denser clay, are versatile and particularly well suited to Green, White, and Oolong teas, where clarity and fragrance are key. Low-fired teapots, which use thicker and more porous clay, retain heat differently and are better suited to Black tea (Red Tea in China) and Pu-Erh tea.

Because a teapot is used repeatedly and often daily, craftsmanship and ergonomics are essential. Look for a pot with no cracks or chips, good weight and balance, and a form that feels natural in the hand. The lid should fit precisely, and the opening should suit the style of tea: smaller openings help retain aroma for small or rolled, highly fragrant leaves, while larger openings work better for large-leaf teas with lower fragrance.

The spout should allow tea to pour freely and quickly. Gongfu Cha relies on short infusion times, so restricted flow can unintentionally lengthen brews. The spout size should be proportional to the pot, and a built-in strainer—or one added inside the spout—helps ensure a clean, even pour.

When choosing a teapot, focus on these four core elements:

-

Size

- Shape

- Manufacture

- Clay Firing

Size

The first consideration when choosing a teapot is size. The ideal teapot should suit the number of people you most often make tea for, as volume directly affects infusion control and flavour balance. While teapots are available in many forms, they can generally be grouped by size as follows:

Volume of Teapot (ml) = Volume of Teacup × Number of People Served

As a simple rule, most traditional teacups hold around 20-30 ml. For example, if you are serving 4 people, a teapot of around 120 ml is sufficient for Gongfu Cha.

Shape

The shape of a teapot impact how tea leaves unfurl and interact with water during brewing. Different forms allow leaves to expand naturally, maximising the surface area exposed to water and supporting a more even extraction. Broadly, teapots fall into two main profiles: high-profile and low-profile with each shape better suited to different styles of tea.

|

Green/White Tea (High Profile) |

|

|

Chinese Black Tea / Pu-Erh (High Profile) |

|

|

Da Hong Pao / Phoenix Tea (Low Profile) |

|

|

Oolong (High Profile) |

|

|

Tie Guan Yin (Low Profile) |

|

Manufacture

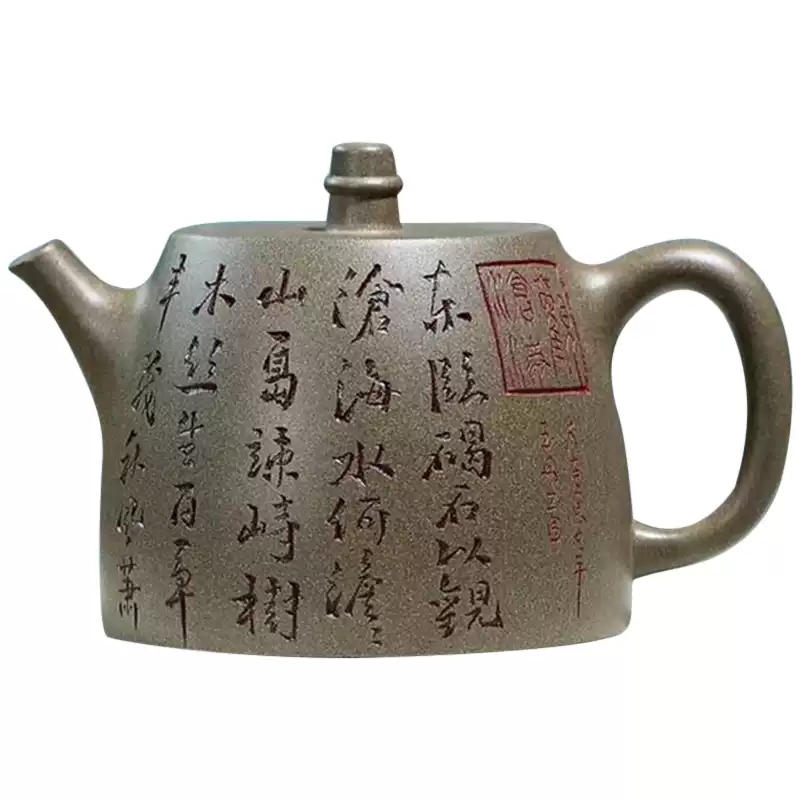

Unlike Western pottery, where softer earth clays are typically thrown on a wheel, Zisha clay is firmer and more structured. This allows a teapot to be formed from individual components-body, spout, handle, and lid-crafted separately and then assembled with precision.

There are three main methods of manufacture:

- Handmade

- Half-handmade

- Molded

Handmade teapots are shaped entirely by the maker. Each component is cut by hand and assembled using traditional tools such as wooden picks and paddles. Before shaping, Zisha clay is repeatedly folded—often compared to the forging of a Japanese katana. This process strengthens the clay and creates fine internal channels, allowing air to move in both directions through the teapot. This natural dual-porosity introduces additional oxygen during brewing, subtly enhancing aroma and flavour.

Half-handmade teapots combine precision and craft. Machine-formed clay pieces are assembled and finished by hand using traditional tools. Many high-quality Yixing teapots are produced this way, offering excellent performance and consistency.

Molded teapots are made through mass production, with pre-molded parts assembled largely by machine. While they hold less artistic value than handmade or half-handmade teapots, many molded teapots still use Yixing clay and perform far better for tea-making than glazed or porcelain vessels.

There is a quiet pride in owning a truly handmade teapot, particularly one crafted by a recognised artist. Teapot making is a highly skilled art, and exceptional Zisha teapots—especially those from the 1950s, 1980s, or the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912)—are sought after by collectors. Each antique carries its own history, patina, and evolving “taste.” Authenticating such pieces requires deep expertise, so antique teapots should only be sourced through specialists you trust.

Clay Firing

Different Zisha clays are fired at different temperatures, and this firing plays a key role in how a teapot performs. Low-fired teapots are made from more porous clay and are typically formed thicker to retain heat for longer periods. This makes them well suited to Chinese Black Tea (Red Tea in China) and Pu-Erh tea, where sustained warmth supports deeper extraction.

High-fired teapots, used for Green, White, and Oolong teas, are made from finer, thinner clay. They cool more quickly, helping prevent these delicate teas from overheating or “cooking” in the pot. Visually, high-fired Zisha clay often appears more reddish, while low-fired clay tends toward brown tones.

In the industry, Zisha clay teapots are typically fired between 1150 °C and 1390 °C, with increments of around 20 °C, resulting in approximately 13 firing intervals. Even small changes within this range can noticeably alter the clay’s structure and behaviour.

In practice, high-fired teapots are less porous and excel at retaining aroma, while low-fired teapots remain more porous and are better suited to teas with heavier bodies and lower fragrance. Firing temperature also affects appearance—the same clay can develop different colours depending on how hot it is fired, adding another layer of variation and character to each teapot

| 1° Interval (1150C) | 3° Interval (1190C) | 6° Interval (1250C) |

|

|

|

Conclusion![]()

Here is a quick checklist to keep in mind when choosing a teapot:

- What type of tea will I be making most often?

- What size teapot do I need for the number of people I usually serve?

- Does the shape allow the tea leaves to expand properly?

- What is the method of manufacture?

- Is the teapot low-fired or high-fired, and does this suit the tea I drink?

- Is the colour consistent with the seller’s description and firing style?

- Are there any chips, cracks, or hidden hairline fractures?

- Is the opening size suitable for the leaf size and fragrance level of the tea?

- Does it have a strainer, and does it pour smoothly?

- Is the teapot well balanced and comfortable to hold?

And most importantly—does the teapot feel right in your hands?

We hope this guide helps you find a teapot that will quietly support your tea practice for years to come. Happy brewing, tea friend.